On May 20th, 2021 the Odeuropa project, in collaboration with Mediamatic, Amsterdam, organized its first workshop, Working with scent in GLAMs: Best Practices and Challenges. The main goal of this workshop was to collect experiences about working with scent in galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAMs), and learn more about the challenges and concerns which may hinder these institutions from working with scent. What knowledge is needed in order for GLAMs to start implementing smell into their programs? How can smell benefit museums and enhance visitor experiences?

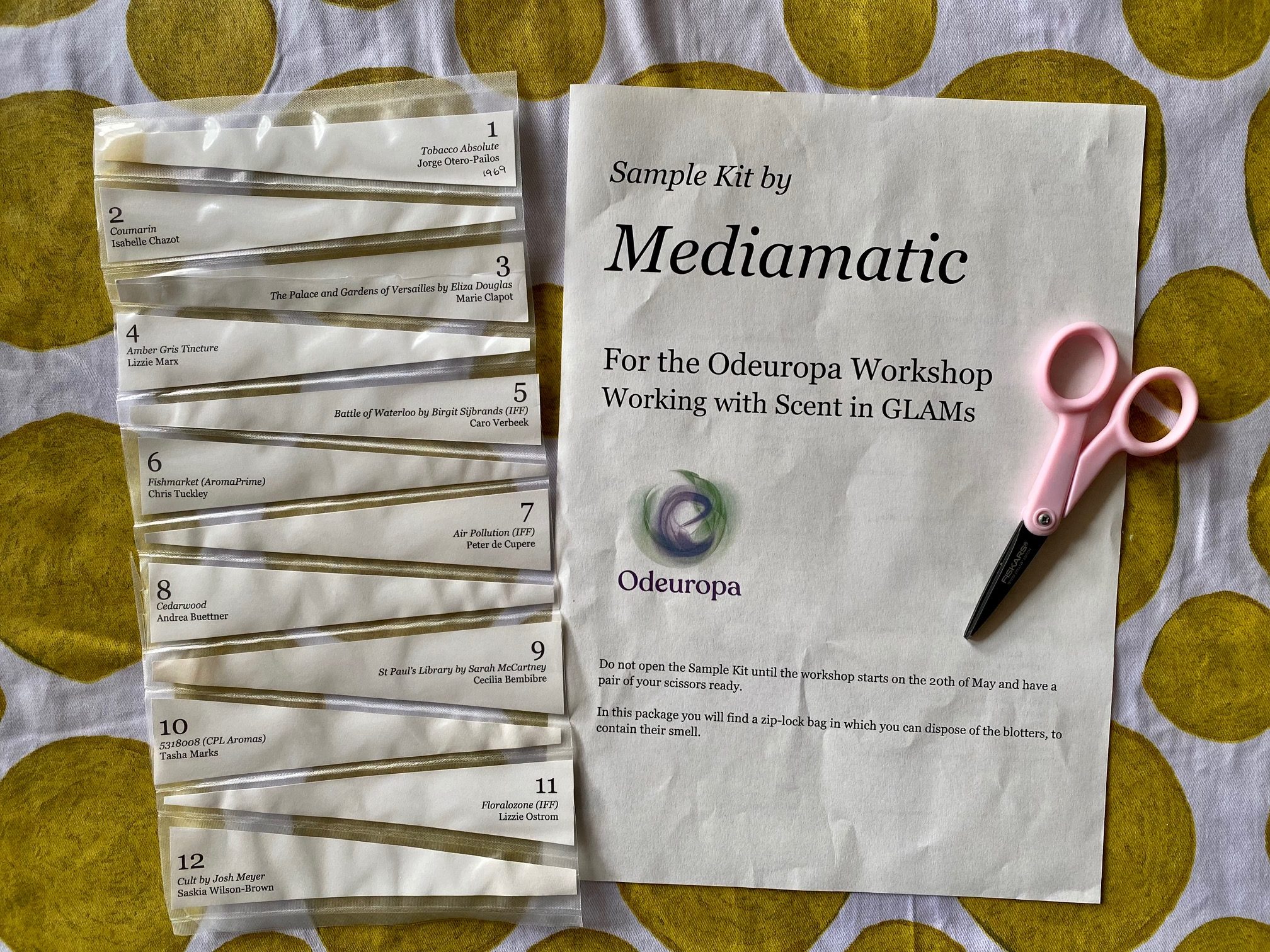

Thirteen experts came together with a range of knowledge about storytelling with and the preservation of (heritage) scents. Their presentations were divided into three panels: 1) Why work with scent in GLAMs? 2) Storytelling (challenges and results) and 3) How to integrate smell into GLAMs? Because of the lockdown, we organized an online workshop that ensured the ‘nose first’ approach Odeuropa has in mind for all its events. Therefore, all speakers were able to pick a scent to accompany their talk which were either chosen from the scent library of Mediamatic, Amsterdam, or provided from the speaker’s own collection. The Mediamatic team (scent designer Frank Bloem, Nour Akoum and Jessica Cohen) created scent kits which could hold 12 different scented blotters, without the scents evaporating or contaminating each other (see image). The kits were sent to the 40 participants (for this first workshop we worked by invitation only, the next workshop will be open to all).

The workshop consisted of 13 ‘lightning talks’ and provided ample opportunity for open discussions. Over 40 participants shared their experiences of working with scent and conveyed ideas about what they think is missing in the industry. The knowledge shared not only focused on the challenges and barriers which face the inclusion of scent into GLAMs, but also on the advantages.

Among the challenges mentioned were difficulties surrounding the safeguarding of heritage scents. Olfactory elements of heritage objects are often disposed of because they are perceived as dangerous to the preservation of the object. It is also difficult to preserve historic scents and perfumes because of their volatile nature. Scents are sensitive and must be protected from exposure to light, heat and oxygen. Additionally, incorporating scents into environments pose conservation concerns. For example, some GLAM professionals are concerned that scents can harm the artworks. Lastly, there is a concern that the incorporation of scent will result in a hedonic reaction from the visitor, defined by the pleasure or displeasure they experience from the scent and the experience.

Despite these challenges, our attendees also offered many advantages. Incorporating smell into GLAMs provides new ways of engaging with the artworks and makes the ‘invisible’ elements of historical depictions ‘visible’ to audiences. The traditional ‘no touch’ and ocularcentric environment of many institutions can separate visitors from the artifacts. Therefore, introducing scent narratives into GLAMs expands knowledge about artworks and historical sites and provides a direct and engaging perspective of the past. This approach not only impacts the memorability of the visit but is also an excellent tool for broadening accessibility efforts, improving inclusivity with different types of audiences.

In conclusion, there is much to be achieved in order to overcome the current challenges which face olfactory GLAM experiences. Our participants proposed a few ways we can overcome these challenges. Firstly, the way smell is presented in relation to an artwork or artifact matters. Any and all context changes a visitor’s perception of the experience and object. Therefore, in addition to conservation and curatorial concerns, all surrounding content and context must be considered. Secondly, the curator, conservation team, and creator of the smell should work together from the beginning in order to avoid conflicts and surprises later. Lastly, trust should be built between scent professionals and GLAMs. This would provide transparency and a sharing of knowledge, easing many concerns that GLAMs have surrounding the incorporation of scent. Through this open communication, a ‘how-to’ guide explaining the do’s and don’ts of olfactory museum practices should be created, providing GLAM professionals access to information about the toxicity, flammability, and conservational risks certain scents pose. The Odeuropa project will develop a Toolkit for Olfactory Storytelling to meet these needs. In our next workshop, we will present the framework for this toolkit to the community, to get feedback and advice. One of the most important things we learned from the workshop is the importance of knowledge sharing as the olfactory heritage field has so many different experts. We are committed to honour their work, while searching new paths for the future.

Speakers and Talk Titles:

Panel #1: Why Work with Smell within GLAMs?

- Jorge Otero Pailos (United States) – An Olfactory Reconstruction of the Philip Johnson Glass House

- Isabelle Chazot (France) – L’Osmothèque: The World’s only Living Perfume Archive

- Marie Clapot (United States) – Olfaction: A Tool towards Democratizing the Museum Experience

- Lizzie Marx (Netherlands) – ‘Fleeting – Scents in Colour’ at the Mauritshuis

Panel #2: Storytelling (challenges and results)

- Caro Verbeek (Netherlands) – Challenges for Tour Guides

- Chris Tuckley (United Kingdom) – Smelly Vikings: Synthetic Fragrances at the JORVIK Viking Centre from 1984 to the Present Day

- Peter de Cupere (Belgium) – The Use of ‘Olfactory Transfers’ in Exhibition Models

- Andrea Buettner (Germany) – Smell: Transporter of Information and Meaning since the Early Beginning of Life

Panel #3: How to integrate smell into GLAMs?

- Cecilia Bembibre (United Kingdom) – Scent of Place: Old Books and Historic Libraries

- Tasha Marks (United Kingdom) – AVM Curiosities & The Sensory Museum

- Lizzie Ostrom (United Kingdom) – How to Tame Your Dragon: Bringing Scent into a Gallery or Museum

- Saskia Wilson Brown (United States) – The Institute of Art & Olfaction