This post by William Tullet originally appeared in The Recipes Project.

A survey of the vast collection in the Wellcome library suggests that the presence of perfumery in manuscript recipe books slowly declined during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Why did this happen? One answer could be that perfumery and pharmacy were slowly separating during the eighteenth century. Previously, perfume, pies, and prescriptions were promiscuously mixed because the boundaries between ‘food’, ‘cosmetics’, and ‘medicines’ were blurred in the 1600s: for instance, odours were thought to contain medical powers. Eighteenth-century physicians were increasingly sceptical about this possibility. Fumigations (to purify the air of houses) and pomanders (balls of perfume to protect against plague) were less common in recipe books by 1750. Perhaps perfume no longer fitted within the holistic tradition of ‘kitchen-physic’. Yet, despite the concerns of the medical profession, perfumes continued to be advertised and used for their medicinal benefits. Fainting dandies at the opera could still reach for the eau de cologne when all the extended vowels and overwhelming music got too much.

Another explanation is the increasing availability of ready-made perfumery, printed recipe books, and an emerging sense of commercial, fashion-oriented, consumer behaviour. Whilst print could easily be incorporated into manuscript recipe books, the proliferation of ready-made perfumery certainly had an impact. Insurance records on Locating London’s Past list over 300 perfumers in London between 1777 and 1786. The influence of the market is detectable in the introductions to print recipe books. For example, Simon Barbe’s The French Perfumer (English translation, London, 1696) lists biblical and noble patrons of perfume to inspire home-brewed perfumery. Charles Lillie’s The British Perfumer (London, 1740s but published 1822) is introduced as a tool for negotiating the commercial market in perfumery: it would help prevent ‘purchasers of perfumes’ from ‘being impose[d] upon… beyond a fair, moderate, and reasonable profit’. Lillie’s book also contains some choice words on domestic perfumery. He attacked those who used ‘scraps of old women’s receipts’ and ‘gleamings from table-talk’. Above all it is fellow perfumers, working for profit in a luxury marketplace, to whom Lillie addresses his recipes.

Lillie’s recipe book has lots to say on how perfumers used their senses to assay the quality of ingredients. The inability to describe odours with precision (except through an emotional vocabulary or by reference to other materials) or remember them easily meant that touch, sight, and taste were thus the chief ways of testing ingredients. Examining ambergris, for example, Lillie noted that the worst was black or dark brown, heavy, hard to break, and had little smell. The best ambergris on the other hand was grey, easy to break and light in weight. If the ambergris had been adulterated with white sand, then Lillie suggested the use of a looking glass to check. Another test involved pricking the material with a hot needle to see if the ‘genuine odour will be given out’. However, Lillie added that ‘best way… to detect such frauds is always for the perfumer to keep by him a small piece of genuine ambergris; and… he should compare their smells by this experiment’. Without the original object smell was never a certain judge.

Where external appearances were similar, as with cassia lignum and cinnamon bark, taste could be used: cinnamon was ‘sharp and biting’ to the taste whereas cassia was ‘sweet and mawkish’. The less salty genoa soap was to the taste, the better quality it was. Touch was mobilised too: clove bark was best when at its most friable, whilst poor quality rice powder, used to make hair powder, was ‘moistened with water to give it a soft and silky feel’. Lillie’s recipe book demonstrates that sensory marks of quality were central for the perfumer because, in an era of economic specialisation, they increasingly relied on druggists, chemists, apothecaries, and grocers for their ingredients. The vanilla-scented gum benjamin (benzoin) was to be had from wax chandlers who used it to perfume sealing wax; druggists were a source for civet, although they adulterated it with honey; and even oils and essences, where the production of commercial quantities required large stills, were to be obtained from chemists ‘who actually distil it themselves’.

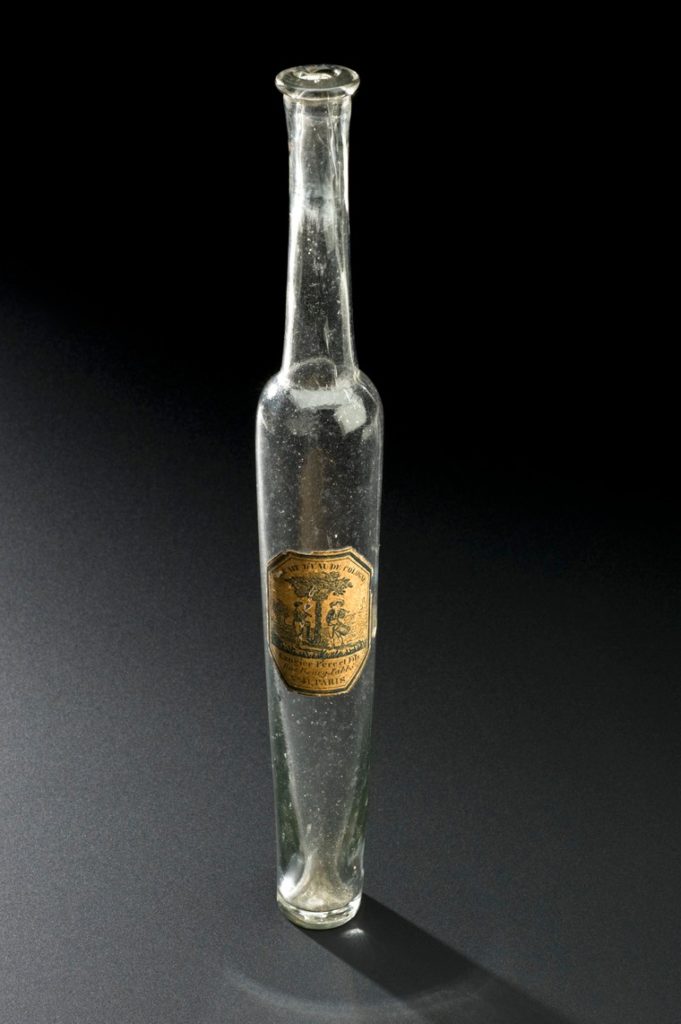

But what about the senses of consumers who bought, rather than made, perfumes? For the small number of individuals who were still making their own perfumery, the perfumer’s shop was important for buying essences and oils ready-made. Mary Forster’s handwritten recipes for soft and hard pomatum, made from hogs’ lard to dress the hair or soften skin, list a range of waters, oils, or essences that could be bought from perfumers and added, depending on preference; these included rose, geranium, and jasmine. Lillie’s book suggests that perfumers were no longer the reliable source of such a wide variety of raw ingredients. Instead they produced ready-made items, some of which – especially waters, essences, and oils – could be used straight away in scent bottles and handkerchiefs or taken home to be used in other recipes. But consumers buying ready-made hair-powder, pomatum, or liquid scents would be far less aware of the colour, texture, weight, and other sensory qualities of the original materials. Perfume advertising also focussed less on particular ingredients and more on the feelings and places the perfumes evoked: in the 1770s Richard Warren’s trade cards evoked biblical frankincense and the odoriferous gales of the east, whilst in 1801, Hester Thrail Piozzia marvelled at the perfumer’s ability to compress ‘India’s fragrance… into a Guinea phial of Odour of Roses’.[1]

What does this tell us about the senses? It might suggest a move closer to a more ‘monolfactory’ (to coin a term) way of smelling, without any sense of a material’s other sensory properties. A loose analogy would be acousmatic listening – where one can hear something but not see the source of the sound (as on the radio). This way of smelling would, during the nineteenth-century, become part of the culture of perfumery we know today – clear, spray-on, liquids that are abstract, aimed at evoking feeling, and carry fewer of the multisensory connotations of the original ingredients. Eighteenth-century recipe books help us trace some of the origins of this slow sensory shift.

[1] Oswald G. Knapp (ed.), The Intimate Letters of Hester Thrale Piozzi and Penelope Pennington, 1788-1821 (London, 1914), p. 229.