The post below by William Tullett originally appeared in The Conversation.

A sunny afternoon in Paris. An intrepid TV presenter is making his way through the streets asking passersby to smell a bottle he has in his hand. When they smell it they react with disgust. One woman even spits on the floor as a marker of her distaste. What is in the bottle? It holds, we are told, the “pong de paris”, a composition designed to smell like an 18th-century Parisian street.

The interpretation of past scents that we are given on the television, perhaps influenced by Patrick Süskind’s pungent novel Perfume, is frequently dominated by offence.

It’s a view found not just on TV but in museums. In England, York’s Jorvik Viking Centre, Hampton Court Palace, and the Museum of Oxfordshire have all integrated smells into their exhibits.

The one smell that unites these attempts at re-odorising the past: toilets. Viking toilets, a Georgian water closet, and the highly urinous and faecal smell of a Victorian street, all included in the above examples, thread the needle of disgust from the medieval to the modern. The consequence of such depictions is to portray the past as an odorous prelude, with foul-smelling trades and poor sanitation, to the clean and pleasant land of modernity.

Suggesting that people who are not “us” stink has a long history. It is applied to our forebears just as often as is to other countries, peoples, or cultures. It is not accident that, “Filthy Cities” – an English television program, highlighted the stink of 18th-century France – even in the 18th century the English had associated the French, their absolutist Catholic enemies, with the stink of garlic.

The toilet-training narrative is a simple and seductive story about “our” conquest of stench. But the “pong de paris” misses the point. Too busy turning the past into a circus of disgust for modern noses, it fails to ask how it smelt to those who lived there. New historical work reveals a more complex story about past scents.

A careful examination of the records of urban government, sanitation, and medicine reveal that 18th-century English city-dwellers were not particularly bothered by unsanitary scents. This was partly because people adapted to the smells around them quickly, to the extent that they failed to notice their presence.

But, thanks to 18th-century scientific studies of air and gases, many Georgians also recognised that bad smells were not as dangerous as had previously been thought. In his home laboratory, the polymath Joseph Priestley experimented on mice, while others used scientific instruments to measure the purity of the air on streets and in bedrooms. The conclusion was simple: smell was not a reliable indicator of danger.

Scientist and social reformer Edwin Chadwick famously claimed in 1846 that “all smell… is disease”. But smell had a much more complex place in miasma theory – the idea that diseases were caused by poisonous airs – than has often been assumed. In fact, by the time cholera began to work its morbid magic in the 1830s, a larger number of medical writers held that smell was not a carrier of sickness-inducing atmospheres.

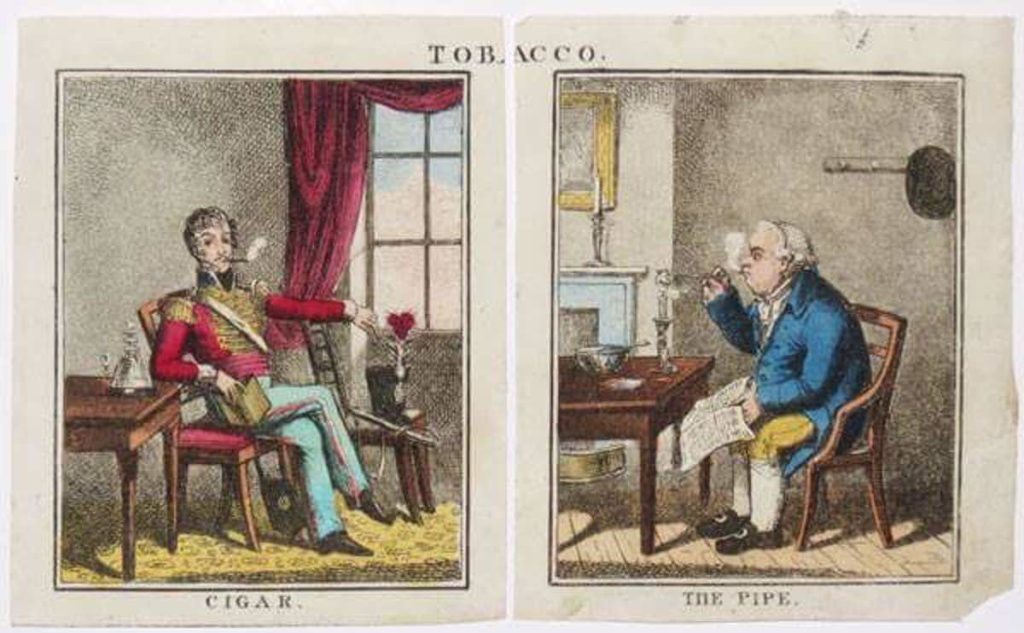

Smells tend to end up in the archive, recorded in the sources historians use, for one of two reasons: either they are unusual (normally offensive) or people decide to pay special attention to them. One scent that appeared in the diaries, letters, magazines, and literature of 18th-century England, however, was tobacco smoke. The 18 century saw the rise of new anxieties about personal space. A preoccupation with politeness in public places would prove a problem for pipe smokers.

Getting sniffy about tobacco

Tobacco had become popular in England during the 17th century. But, by the mid-18th century, qualms began to be raised. Women were said to abhor the smell of tobacco smoke. A satirical poem told the story of a wife who had banned her husband from smoking, only to allow its resumption – she realised that going cold turkey had made him impotent.

New sociable venues proliferated in towns and cities, with the growth of provincial theatres, assembly rooms, and pleasure gardens. In these sociable spaces, a correspondent to The Monthly Magazine noted in 1798, “smoaking [sic] was a vulgar, beastly, unfashionable, vile thing” and “would not be suffered in any genteel part of the world”. Tobacco smoking was left to alehouses, smoking clubs and private masculine spaces.

Clouds of smoke invaded people’s personal space, subjecting them to atmospheres that were not of their own choosing. Instead, fashionable 18th-century nicotine addicts turned to snuff. Despite the grunting, hawking and spitting it encouraged, snuff could be consumed without enveloping those around you in a cloud of sour smoke.

The 18th century gave birth to modern debates about smoking and public space that are still with us today. The fact that the smell of tobacco smoke stains the archives of the period, metaphorically of course, is a testament to the new ideas of personal space that were developing within it.