This post by Caro Verbeek originally appeared on the Futurist Scents blog.

About 6 weeks ago – shortly before the ‘intelligent lockdown’ – the familiar smells that characterize my neighborhood in the west of Amsterdam suddenly changed. Not in an unpleasant way, but quite dramatically. I followed my nose and wound up at the small grocery store where I usually do my shopping. A strong refreshing scent seemed to emanate from it, covering the entire block. I figured it was a citrus fruit of some sort, but it was extraordinarily strong.

Upon asking the shopkeeper he promptly replied: “It’s cologne from my home country Turkey. I use it to stay clean!”, and he showed me how he did it by applying some of the liquid lavishly on his hands directly from a big bottle. I wondered if this sudden change of habit, perceivable outside his shop, was connected to the outbreak of Corona. It was. The next day I read in a news item that the phenomenon I had noticed on a local scale, was taking place on an international level. Even the BBC recently picked it up. They merely focused on the economic impact though. But there is so much more to it.

The zesty smell is so well-known and typical for the country, that a national representative – when asked by artist Gayil Nalls what the national scent of Turkey could be – said that:

“The scents of lavender and pine grow lavishly in Turkey. However, if you must choose the most applicable of fragrances, the lemon and rose are certainly the ones that are most popularly used. And of those, Turkey would be represented by lemon. It’s everywhere. The lemon cologne is sprayed on you, given to you, 100% of Turkish people have lemon cologne in their homes. Lemon is a very culturally important smell for us” (Birnur Fertekigil, Counselor and Staff, Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations, you can read more about the olfactory social sculpture World Sensorium and find out which scent was selected by your country here)

The BBC reported that the renewed purpose of cologne was novel, but its practical and medicinal use actually has a long tradition that actually wasn’t lost at all: “I associate lemon with being ill”, a Turkish museum expert had told me during a meeting just a few days prior to the lockdown. “Whenever I was sick as a child my mother gave me cologne”.

In fact, when the first cologne (by the Italian barber Gian Paolo de Feminis and Farina, not by 4711) was marketed in the city of Cologne, it was already promoted as a miracle water, a cure-all elixir, or ‘aqua mirabilis’ as literary historian Richard Stamelan explains:

“In an early attempt of self-promoting hyperbole, Feminis’s “miraculous” water was advertised as a remedy for problems the stomach, skin and even for women going into labour” (2006)

The shift from the medicinal to the aesthetic use of eau de Cologne must have occurred in the 19th century:

“Although eau de Cologne was originally introduced to the public as a sort of “cure-all,” a regular “elixir of life,” it now takes its place, not as a pharmaceutical product, but among perfumery” (Septimus Piesse, 1857).

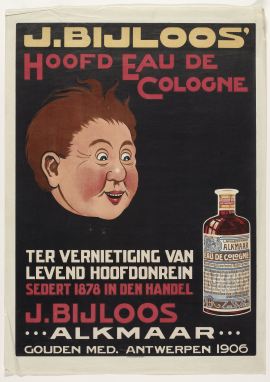

But while advertisements from the 20th century, there are plenty of examples of the medicinal use of eau de Cologe. Apparently it could kill lice as this example from the collection of the Rijksmuseum shows.

Eau de Cologne is the oldest still marketed scented product. The recent rise in sales shouldn’t just be explained as an economic phenomenon, but as a historical and cultural development. Its use is as versatile as it is intriguing, and it perceivably connects the present to the past, especially today.

Read more about the history of Turkish cologne here.