(written by Sara Tonelli)

One of the main goals of Odeuropa has been understanding how smell perception has changed over time. Using the system for olfactory information extraction developed within the project, this kind of analysis has now become possible. A first exploration was carried out using a collection of freely available corpora in English, covering a period between 1500 and 2000. Such collection includes London Pulse Medical Records, the Early English Books online and Wikisource, among others. We selected some items which are particularly relevant to European olfactory history, such as incense, candles, gloves, tobacco and ozone, with the goal to analyse how the description of their smell has changed over time.

We first launched the Odeuropa system for olfactory information extraction on the corpora collection mentioned above, in order to capture all mentions of the items, as well as their association with some smells. An overview of this first analysis is displayed below:

![]()

For each item, the graph displays the percentage of mentions in our corpus that are labelled also as smell source. In short, a peak in the graph corresponds to a time period in which a term was strongly associated with the olfactory domain. For instance, history scholars showed that leather gloves in the 17th Century used to be scented with perfumes to temper their bad smell coming from compounds used to make leather softer. Thus, they were seen as strong olfactory objects at the time, while nowadays they are not considered ‘smelly’ items. Overall, incense is the item that is most associated with the olfactory domain, in particular around 1860 and 1970, when almost 40% of its mentions are smell-related. The graph for candle(s), instead, displays a growth after 1960, probably related to the widespread use of scented candles. As regards glove(s), the graph shows that it stops being perceived as an olfactory object after 1950, but that nevertheless it was characterised as smell-related only rarely before that date (less than 2% of the mentions). Finally, tobacco and ozone are more ‘modern’ smells, in particular the latter, which was first used to characterise the aroma resulting from experiments with electricity around 1840 and later started being associated with ozone depletion, losing its odorous connotation.

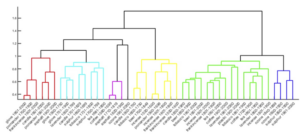

In a second analysis, we aimed at identifying perceptions shifts of different smell sources. Therefore, we created for each item in a given time span a vector embedding containing the PMI (pointwise-mutual information) values of association between such item and a fixed set of olfactory qualities (e.g. fragrant, pungent, sweet). Then, we ran a hierarchical clustering algorithm to identify groups of items that, in a given time span, were described in a similar way. The output is displayed below.

The dendogram shows that the vectors of the same item in different time periods are often far apart and belong to different clusters, as can be observed for gloves, ozone and incense / frankincense. The last two terms, in particular, were considered interchangeable in the past (see yellow and green cluster), but from the beginning of the twentieth century frankincense seems to be used in different contexts (red cluster).

This work shows a novel approach, which combines the power of olfactory information extraction in depicting semantic context and the tradition of semantic change detection to explore the evolution of olfactory language from a diachronic perspective.

A demonstrator of the system for olfactory information extraction can be accessed here: https://smell-extractor.tools.eurecom.fr/

The list of smell sources and the PMI-based vectors used to perform the clustering are available here: https://github.com/dhfbk/scent-change

For a full analysis description, see:

Teresa Paccosi, Stefano Menini, Elisa Leonardelli, Ilaria Barzon, Sara Tonelli. Scent and Sensibility: Perception Shifts in the Olfactory Domain. Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Computational Approaches to Historical Language Change 2023 (LChange 23).