Linguists have observed in several studies that languages seem to have a smaller vocabulary to describe smells compared to other senses. Odours are often described borrowing terms from other senses, for example “sweet” or “fresh”, or relying on qualities of objects, like “musky” or “metallic”. On the other hand, other domains such as perfumery and oenology make use of extremely precise and structured repositories of terms and qualities used by professionals for describing perfumes and wines from an olfactory perspective. One of the goals of the text processing team of Odeuropa is to understand these phenomena and analyse whether there are differences across languages in the way in which odours are described. Is the smell-related dimension of the olfactory vocabulary something that is more evident in some languages? For example, does Slovenian, which is a Balto-Slavic language, have different characteristics in terms of olfactory vocabulary compared to Romance or Germanic languages like Italian and English? If ‘yes’, are there historical or cultural reasons for this?

We aim to address these questions using text mining techniques by processing large amounts of digitised texts covering four centuries and automatically extracting the terminology pertaining to smell. To this purpose, we are collecting freely available texts issued between 1650 and 1925 and covering different domains, in the seven project languages (English, German, French, Latin, Dutch, Slovene, and Italian). These texts range from travel literature to scientific texts and medical records. This process takes a long time because after preparing a detailed list of available sources, the data need to be downloaded, cleaned, standardised and accompanied with the correct metadata. While the Odeuropa multilingual corpus is being completed, we are testing different approaches to terminology extraction. Our testbed is the GoogleNgram repository, a large collection of n-grams (i.e. word sequences) extracted from Google Books divided by year of publication.

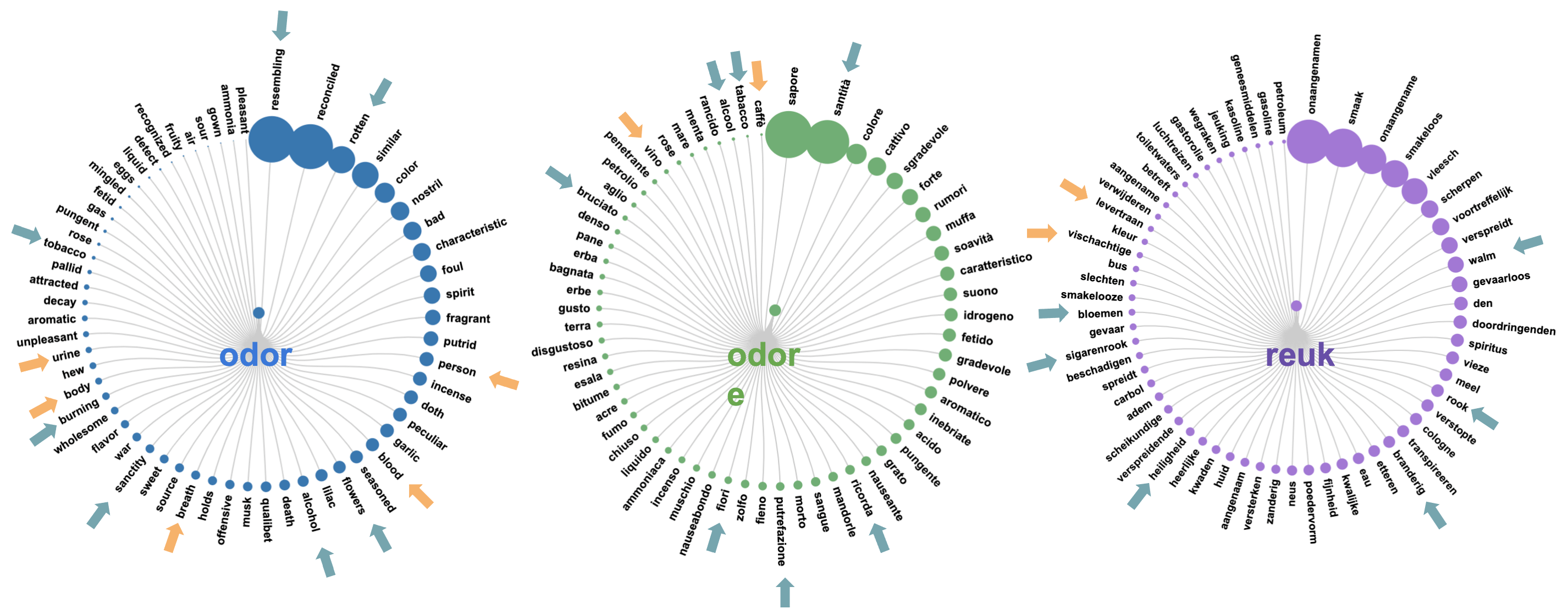

The n-grams cover the period of interest for Odeuropa, allowing us to perform preliminary analyses aimed at comparing terminology in multiple languages over time. In this analysis, we start from a small list of smell-related words provided by Odeuropa domain experts such as “odour”, “smelly”, “reek”. We then extract for different time periods the terms that have the highest association strength with the smell words, meaning that they tend to appear together more frequently than usual. Terms co-occurring with the smell words provide a concise overview of the semantic domains associated with odours over time, and make comparisons across languages possible. For example, we can analyse terms related to “odor” (English) , “odore” (Italian) and “reuk” (Dutch) for the n-grams between 1900 and 1925. These are displayed in the picture below, where the bubble dimension is proportional to the association strength. Some concepts mentioned in relation to smell seem to be present for the three languages, for example flowers, tobacco and sanctity. On the other hand, in English, medical-related terms are more present, while for Italian food and beverages are mentioned (see also “sapore” / “taste”) and for Dutch, fishing seems to play a role in the word association. For now, our results are too preliminary to draw conclusions on olfactory terminology, but we are really looking forward to understanding what texts from the past tell us about odours and their story.